Pre-twentieth century

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, mostly using

one-to-one correspondence with

fingers. The earliest counting device was probably a form of

tally stick. Later record keeping aids throughout the

Fertile Crescent included calculi (clay spheres, cones, etc.) which represented counts of items, probably livestock or grains, sealed in hollow unbaked clay containers.

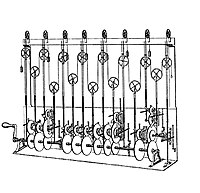

[4][5] The use of

counting rods is one example.

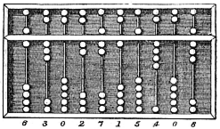

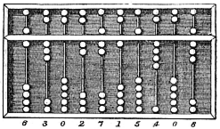

Suanpan (the number represented on this abacus is 6,302,715,408)

The

abacus was initially used for arithmetic tasks. The

Roman abacus was used in

Babylonia as early as 2400 BC. Since then, many other forms of reckoning boards or tables have been invented. In a medieval European

counting house, a checkered cloth would be placed on a table, and markers moved around on it according to certain rules, as an aid to calculating sums of money.

The ancient Greek-designed

Antikythera mechanism, dating between 150 to 100 BC, is the world's oldest analog computer.

The

Antikythera mechanism is believed to be the earliest mechanical analog "computer", according to

Derek J. de Solla Price.

[6] It was designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in 1901 in the

Antikythera wreckoff the Greek island of

Antikythera, between

Kythera and

Crete, and has been dated to

circa 100 BC. Devices of a level of complexity comparable to that of the Antikythera mechanism would not reappear until a thousand years later.

The

sector, a calculating instrument used for solving problems in proportion, trigonometry, multiplication and division, and for various functions, such as squares and cube roots, was developed in the late 16th century and found application in gunnery, surveying and navigation.

The

planimeter was a manual instrument to calculate the area of a closed figure by tracing over it with a mechanical linkage.

The

slide rule was invented around 1620–1630, shortly after the publication of the concept of the

logarithm. It is a hand-operated analog computer for doing multiplication and division. As slide rule development progressed, added scales provided reciprocals, squares and square roots, cubes and cube roots, as well as

transcendental functions such as logarithms and exponentials, circular and hyperbolic trigonometry and other

functions. Aviation is one of the few fields where slide rules are still in widespread use, particularly for solving time–distance problems in light aircraft. To save space and for ease of reading, these are typically circular devices rather than the classic linear slide rule shape. A popular example is the

E6B.

In the 1770s

Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a Swiss

watchmaker, built a mechanical doll (

automata) that could write holding a quill pen. By switching the number and order of its internal wheels different letters, and hence different messages, could be produced. In effect, it could be mechanically "programmed" to read instructions. Along with two other complex machines, the doll is at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire of

Neuchâtel,

Switzerland, and still operates.

[14]

The

tide-predicting machine invented by

Sir William Thomson in 1872 was of great utility to navigation in shallow waters. It used a system of pulleys and wires to automatically calculate predicted tide levels for a set period at a particular location.

The

differential analyser, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve

differential equations by

integration, used wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. In 1876

Lord Kelvin had already discussed the possible construction of such calculators, but he had been stymied by the limited output torque of the

ball-and-disk integrators.

[15] In a differential analyzer, the output of one integrator drove the input of the next integrator, or a graphing output. The

torque amplifier was the advance that allowed these machines to work. Starting in the 1920s,

Vannevar Bush and others developed mechanical differential analyzers.

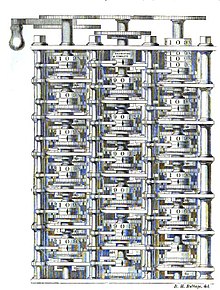

First general-purpose computing device

Charles Babbage, an English mechanical engineer and

polymath, originated the concept of a programmable computer. Considered the "

father of the computer",

[16] he conceptualized and invented the first

mechanical computer in the early 19th century. After working on his revolutionary

difference engine, designed to aid in navigational calculations, in 1833 he realized that a much more general design, an

Analytical Engine, was possible. The input of programs and data was to be provided to the machine via

punched cards, a method being used at the time to direct mechanical

looms such as the

Jacquard loom. For output, the machine would have a printer, a curve plotter and a bell. The machine would also be able to punch numbers onto cards to be read in later. The Engine incorporated an

arithmetic logic unit,

control flow in the form of

conditional branching and

loops, and integrated

memory, making it the first design for a general-purpose computer that could be described in modern terms as

Turing-complete.

[17][18]

The machine was about a century ahead of its time. All the parts for his machine had to be made by hand — this was a major problem for a device with thousands of parts. Eventually, the project was dissolved with the decision of the

British Government to cease funding. Babbage's failure to complete the analytical engine can be chiefly attributed to difficulties not only of politics and financing, but also to his desire to develop an increasingly sophisticated computer and to move ahead faster than anyone else could follow. Nevertheless, his son, Henry Babbage, completed a simplified version of the analytical engine's computing unit (the

mill) in 1888. He gave a successful demonstration of its use in computing tables in 1906.

Later Analog computers

During the first half of the 20th century, many scientific

computing needs were met by increasingly sophisticated

analog computers, which used a direct mechanical or electrical model of the problem as a basis for

computation. However, these were not programmable and generally lacked the versatility and accuracy of modern digital computers.

[19]

The art of mechanical analog computing reached its zenith with the

differential analyzer, built by H. L. Hazen and

Vannevar Bush at

MITstarting in 1927. This built on the mechanical integrators of

James Thomson and the torque amplifiers invented by H. W. Nieman. A dozen of these devices were built before their obsolescence became obvious.

By the 1950s the success of digital electronic computers had spelled the end for most analog computing machines, but analog computers remain in use in some specialized applications such as education (

control systems) and aircraft (

slide rule).

Digital computer development

The principle of the modern computer was first described by

mathematician and pioneering

computer scientist Alan Turing, who set out the idea in his seminal 1936 paper,

[20] On Computable Numbers. Turing reformulated

Kurt Gödel's 1931 results on the limits of proof and computation, replacing Gödel's universal arithmetic-based formal language with the formal and simple hypothetical devices that became known as

Turing machines. He proved that some such machine would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical computation if it were representable as an

algorithm. He went on to prove that there was no solution to the

Entscheidungsproblem by first showing that the

halting problem for Turing machines is

undecidable: in general, it is not possible to decide algorithmically whether a given Turing machine will ever halt.

He also introduced the notion of a 'Universal Machine' (now known as a

Universal Turing machine), with the idea that such a machine could perform the tasks of any other machine, or in other words, it is provably capable of computing anything that is computable by executing a program stored on tape, allowing the machine to be programmable.

Von Neumann acknowledged that the central concept of the modern computer was due to this paper.

[21] Turing machines are to this day a central object of study in

theory of computation. Except for the limitations imposed by their finite memory stores, modern computers are said to be

Turing-complete, which is to say, they have

algorithm execution capability equivalent to a

universal Turing machine.

Electromechanical

By 1938 the

United States Navy had developed an electromechanical analog computer small enough to use aboard a

submarine. This was the

Torpedo Data Computer, which used trigonometry to solve the problem of firing a torpedo at a moving target. During

World War II similar devices were developed in other countries as well.

Replica of

Zuse's

Z3, the first fully automatic, digital (electromechanical) computer.

Early digital computers were electromechanical; electric switches drove mechanical relays to perform the calculation. These devices had a low operating speed and were eventually superseded by much faster all-electric computers, originally using

vacuum tubes. The

Z2, created by German engineer

Konrad Zuse in 1939, was one of the earliest examples of an electromechanical relay computer.

[22]

In 1941, Zuse followed his earlier machine up with the

Z3, the world's first working

electromechanical programmable, fully automatic digital computer.

[23][24] The Z3 was built with 2000

relays, implementing a 22

bit word length that operated at a

clock frequency of about 5–10

Hz.

[25]Program code was supplied on punched

film while data could be stored in 64 words of memory or supplied from the keyboard. It was quite similar to modern machines in some respects, pioneering numerous advances such as

floating point numbers. Replacement of the hard-to-implement decimal system (used in

Charles Babbage's earlier design) by the simpler

binary system meant that Zuse's machines were easier to build and potentially more reliable, given the technologies available at that time.

[26] The Z3 was probably a complete

Turing machine.

Vacuum tubes and digital electronic circuits

Purely

electronic circuit elements soon replaced their mechanical and electromechanical equivalents, at the same time that digital calculation replaced analog. The engineer

Tommy Flowers, working at the

Post Office Research Station in

London in the 1930s, began to explore the possible use of electronics for the

telephone exchange. Experimental equipment that he built in 1934 went into operation 5 years later, converting a portion of the

telephone exchange network into an electronic data processing system, using thousands of

vacuum tubes.

[19] In the US, John Vincent Atanasoff and Clifford E. Berry of Iowa State University developed and tested the

Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC) in 1942,

[27] the first "automatic electronic digital computer".

[28] This design was also all-electronic and used about 300 vacuum tubes, with capacitors fixed in a mechanically rotating drum for memory.

[29]

During World War II, the British at

Bletchley Park achieved a number of successes at breaking encrypted German military communications. The German encryption machine,

Enigma, was first attacked with the help of the electro-mechanical

bombes. To crack the more sophisticated German

Lorenz SZ 40/42 machine, used for high-level Army communications,

Max Newman and his colleagues commissioned Flowers to build the

Colossus.

[29] He spent eleven months from early February 1943 designing and building the first Colossus.

[30] After a functional test in December 1943, Colossus was shipped to Bletchley Park, where it was delivered on 18 January 1944

[31] and attacked its first message on 5 February.

[29]

Colossus was the world's first

electronic digital programmable computer.

[19] It used a large number of valves (vacuum tubes). It had paper-tape input and was capable of being configured to perform a variety of

boolean logical operations on its data, but it was not

Turing-complete. Nine Mk II Colossi were built (The Mk I was converted to a Mk II making ten machines in total). Colossus Mark I contained 1500 thermionic valves (tubes), but Mark II with 2400 valves, was both 5 times faster and simpler to operate than Mark 1, greatly speeding the decoding process.

[32][33]

ENIAC was the first Turing-complete device, and performed ballistics trajectory calculations for the

United States Army.

The US-built

ENIAC[34] (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first electronic programmable computer built in the US. Although the ENIAC was similar to the Colossus it was much faster and more flexible. It was unambiguously a Turing-complete device and could compute any problem that would fit into its memory. Like the Colossus, a "program" on the ENIAC was defined by the states of its patch cables and switches, a far cry from the

stored program electronic machines that came later. Once a program was written, it had to be mechanically set into the machine with manual resetting of plugs and switches.

It combined the high speed of electronics with the ability to be programmed for many complex problems. It could add or subtract 5000 times a second, a thousand times faster than any other machine. It also had modules to multiply, divide, and square root. High speed memory was limited to 20 words (about 80 bytes). Built under the direction of

John Mauchly and

J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania, ENIAC's development and construction lasted from 1943 to full operation at the end of 1945. The machine was huge, weighing 30 tons, using 200 kilowatts of electric power and contained over 18,000 vacuum tubes, 1,500 relays, and hundreds of thousands of resistors, capacitors, and inductors.

[35]

Stored programs

The Mark 1 in turn quickly became the prototype for the

Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercially available general-purpose computer.

[39]Built by

Ferranti, it was delivered to the

University of Manchester in February 1951. At least seven of these later machines were delivered between 1953 and 1957, one of them to

Shell labs in

Amsterdam.

[40] In October 1947, the directors of British catering company

J. Lyons & Company decided to take an active role in promoting the commercial development of computers. The

LEO I computer became operational in April 1951

[41] and ran the world's first regular routine office computer

job.

Transistors

The bipolar

transistor was invented in 1947. From 1955 onwards transistors replaced

vacuum tubes in computer designs, giving rise to the "second generation" of computers. Compared to vacuum tubes, transistors have many advantages: they are smaller, and require less power than vacuum tubes, so give off less heat. Silicon junction transistors were much more reliable than vacuum tubes and had longer, indefinite, service life. Transistorized computers could contain tens of thousands of binary logic circuits in a relatively compact space.

Integrated circuits

The first practical ICs were invented by

Jack Kilby at

Texas Instruments and

Robert Noyce at

Fairchild Semiconductor.

[47] Kilby recorded his initial ideas concerning the integrated circuit in July 1958, successfully demonstrating the first working integrated example on 12 September 1958.

[48] In his patent application of 6 February 1959, Kilby described his new device as "a body of semiconductor material ... wherein all the components of the electronic circuit are completely integrated".

[49][50] Noyce also came up with his own idea of an integrated circuit half a year later than Kilby.

[51] His chip solved many practical problems that Kilby's had not. Produced at Fairchild Semiconductor, it was made of

silicon, whereas Kilby's chip was made of

germanium.

This new development heralded an explosion in the commercial and personal use of computers and led to the invention of the

microprocessor. While the subject of exactly which device was the first microprocessor is contentious, partly due to lack of agreement on the exact definition of the term "microprocessor", it is largely undisputed that the first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004,

[52] designed and realized by

Ted Hoff,

Federico Faggin, and Stanley Mazor at

Intel.

[53]

Mobile computers become dominant

With the continued miniaturization of computing resources, and advancements in portable battery life,

portable computers grew in popularity in the 2000s.

[54] The same developments that spurred the growth of laptop computers and other portable computers allowed manufacturers to integrate computing resources into cellular phones. These so-called

smartphones and

tablets run on a variety of operating systems and have become the dominant computing device on the market, with manufacturers reporting having shipped an estimated 237 million devices in 2Q 2013.

[55]

copy righthttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer